Helen Hunt Jackson - Inspiring A Nation

Helen Hunt Jackson - Inspiring A Nation

by Nancy Bradshaw

In that vast, sweeping theater of the American West, where the stark, unyielding beauty of the landscape confronted the raw, often brutal, realities of a nation’s westward march, there emerged a voice. A singular voice, marked by an unwavering conviction, a voice utterly devoted to the cause of a people too often unseen, unheard. That voice belonged to Helen Hunt Jackson, a woman whose own life, etched with the deep scars of personal loss, would ultimately find its truest purpose in her passionate, unyielding advocacy for the Native American people. Her very being seemed to resonate with a profound empathy for their plight.

Born Helen Maria Fiske in 1830, in the quiet, intellectual enclave of Amherst, Massachusetts, she was a product of her time, steeped in the rich, vibrant currents of New England thought. Yet, life, as it often does, dealt her a series of cruel, unrelenting blows. The untimely loss of her first husband, Edward Hunt, and then the heart-rending deaths of her two sons, cast a long, somber shadow, a profound grief that, in time, would forge within her a steely resolve. It was as if, from the very ashes of her own profound sorrow, she found a burning, almost incandescent, empathy for the suffering of others, a suffering she would soon witness on a far grander scale.

Her journey westward, a quest for solace and the restorative balm of the crisp Colorado air, proved to be a transformative experience. What she witnessed there, however, was not the idealized, romanticized vision of the frontier, but a stark, unvarnished tableau of injustice. The systematic dispossession of Native American lands, the broken treaties, the callous, almost indifferent disregard for human dignity—these were the realities that seized her conscience, that would not, could not, be ignored. Her heart, it seemed, had found its true north in the defense of these marginalized souls.

And so, she took up her pen, not as a weapon of destruction, but as a tool of truth, a finely honed instrument of revelation. In “A Century of Dishonor,” she laid bare the grim, unconscionable record of the United States government’s dealings with the Native American tribes, a damning indictment of broken promises and betrayed trust. It was a work of meticulous research, a passionate plea for justice, and a clarion call to the nation’s conscience, fueled by her deep and abiding commitment to these first peoples of the land.

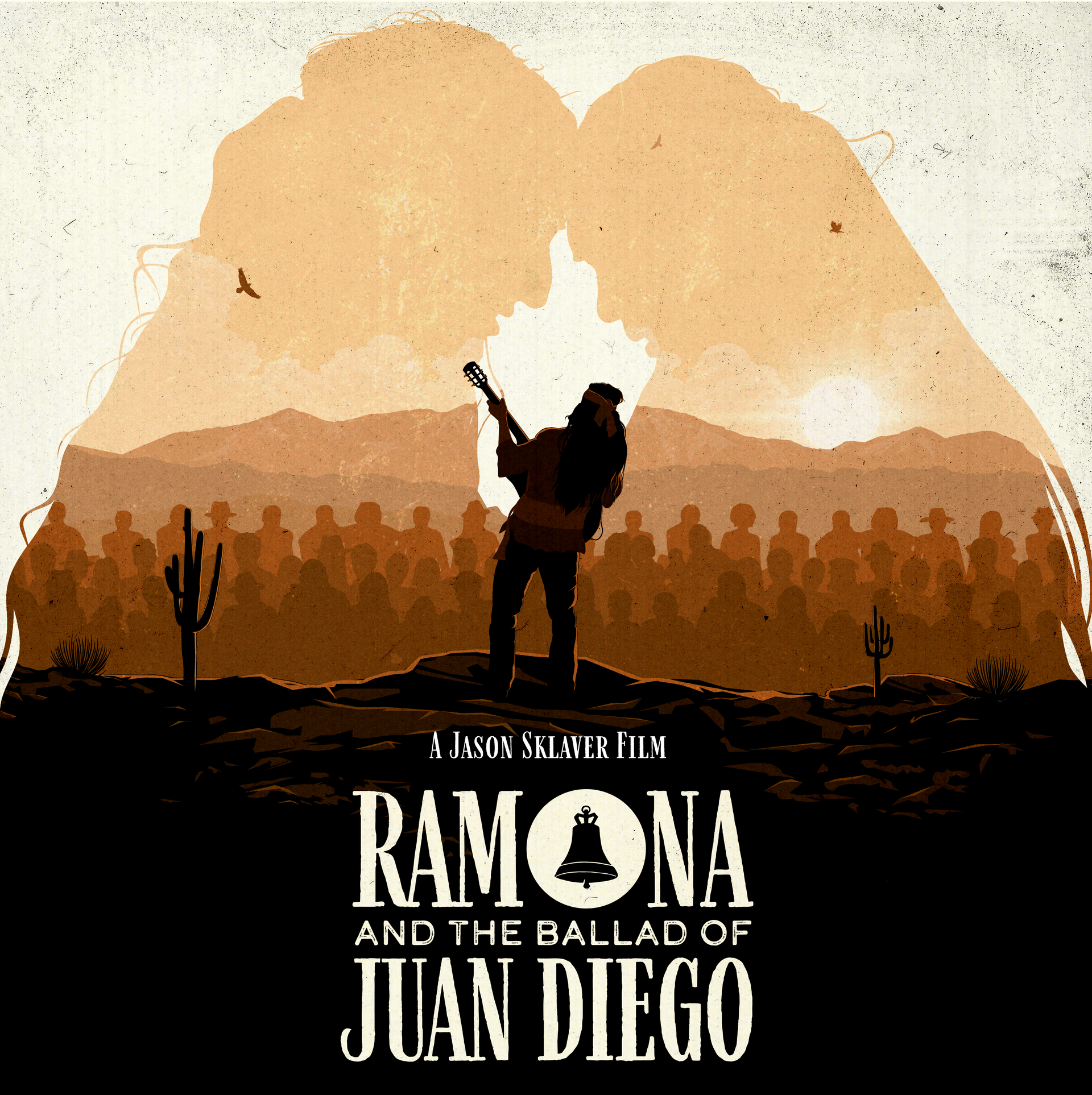

Then came “Ramona,” a novel, a work of fiction, yet a powerful, poignant testament to the plight of the Mission Indians of Southern California. These Mission Indians, a collective term for the Native American tribes profoundly influenced by the Spanish missions established from the 18th to the early 19th centuries, included the Chumash, Tongva, Luiseño, Kumeyaay, Cahuilla, Serrano, and Cupeño. These tribes, compelled into mission life, endured cultural and social upheaval, their traditional ways disrupted, their lives forever altered. Helen Hunt Jackson, with her unwavering focus, sought to give voice to their silent suffering.

In 1883, Jackson, appointed by the Interior Department, embarked on an investigation into the conditions of these Mission Indians, collaborating with Abbott Kinney. Her travels through Riverside and San Diego counties revealed the stark, undeniable realities of poverty and the devastating loss of land, particularly among the former Gabrieliño, Luiseño, and Diegueño/Kumeyaay groups. This firsthand experience, this immersion in the lives of those she sought to defend with such fierce dedication, provided vital, irrefutable material for her later works, most notably, “Ramona.” Her commitment was not from a distance, but born of direct observation and a profound connection to the individuals she encountered.

The novel “Ramona” was profoundly inspired by her interactions with these tribes and a specific, tragic event involving the Cahuilla. The story of a Cahuilla woman and her husband, whose 1883 murder by a white man following a dispute over a horse, became a poignant, unforgettable catalyst. These events inspired Jackson to craft a narrative that brought to light the injustices faced by Native Americans. In the novel, the character Alessandro, Ramona’s husband, is from the Luiseño tribe, specifically from Temecula, reflecting their struggles with land dispossession and the relentless encroachment of settlers. At the novel’s conclusion, Ramona finds refuge with the Cahuilla tribe, further emphasizing their role in the narrative. Through this fictional tale, Jackson sought to awaken the nation’s heart to the very real anguish of these communities.

The novel, set in the post-Mexican-American War Southern California, was intended to evoke sympathy for Native Americans, much like “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” did for the enslaved African Americans. While the Luiseño tribe is central through Alessandro, the Cahuilla’s role is tied to the real-life inspiration and the novel’s conclusion. “Ramona” achieved remarkable commercial success, being reprinted over 300 times and boosting Southern California tourism as readers sought out locations from the book. Yet, for Jackson, the true measure of its success lay in its potential to stir compassion and ignite a demand for justice for the people to whom she had so completely dedicated her efforts.

However, while it raised awareness, it did not immediately translate into policy changes, with many readers focusing on the romantic aspects rather than the political message. Jackson’s work, including her report on the Mission Indians, influenced later reform groups like the Indian Rights Association, leaving a lasting impact on Native American advocacy. The description of the play as a “Romeo and Juliet that is set in the Wild Wild West” effectively encapsulates the blend of a timeless love story with a specific and dramatic historical context, explaining its enduring power.

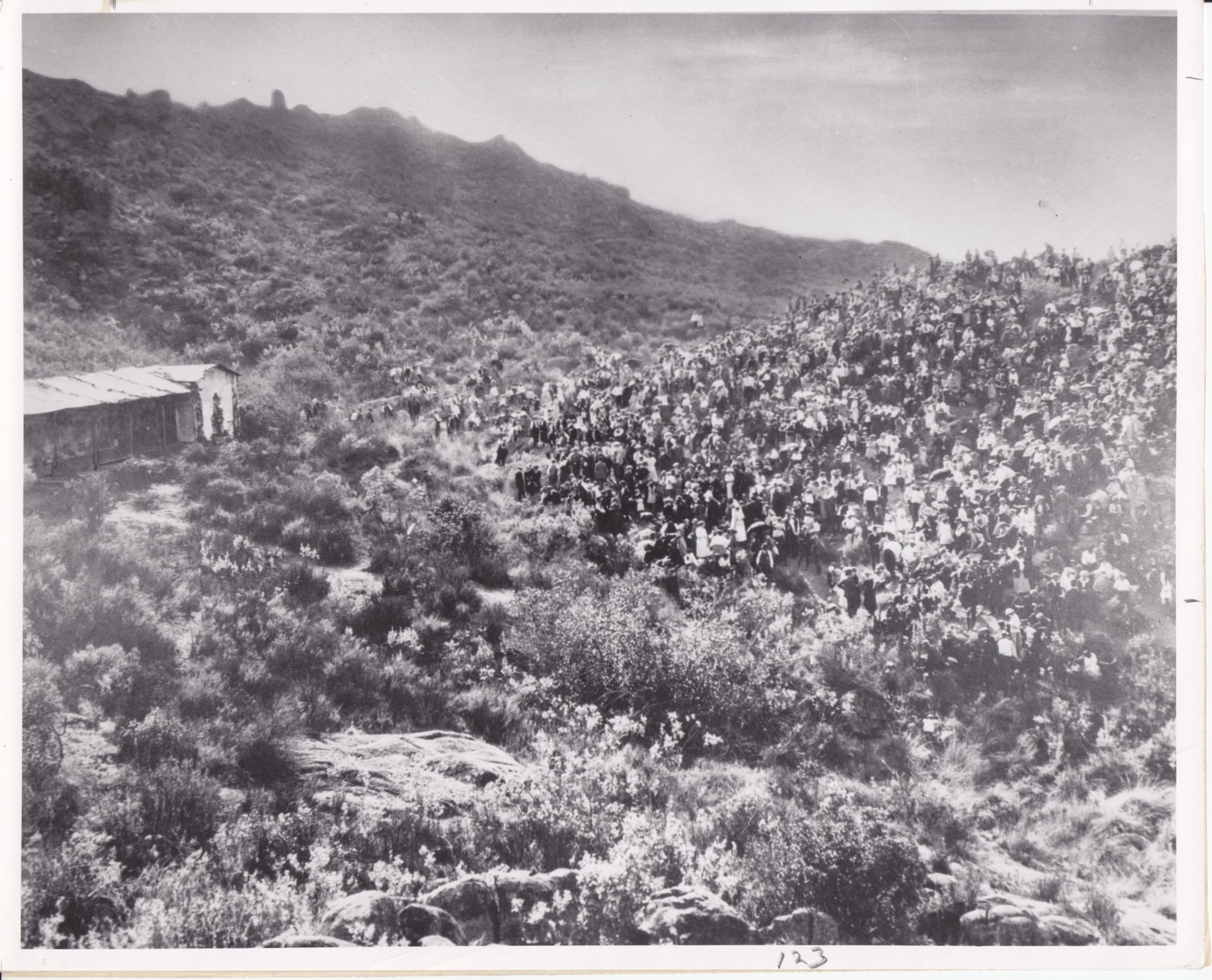

The transition of “Ramona” from the written page to the outdoor stage occurred in 1923, thanks to the vision of Garnet Holme. Holme not only adapted the novel into a play but also took on the role of the original director and selected the very location for its performance: the natural amphitheater known as the Ramona Bowl in Hemet. This choice of an outdoor setting was crucial, as it allowed for a grand spectacle that mirrored the expansive landscapes of early California, providing an immersive experience for the audience. The premiere of “The Ramona Pageant” on April 13, 1923, in Hemet marked the beginning of an annual tradition that has, with very few exceptions due to significant historical events, continued uninterrupted for over a century. This annual performance stands as a testament to the enduring resonance of Jackson’s heartfelt narrative.

After decades of captivating audiences and establishing itself as a significant cultural event in California, “The Ramona Pageant” received official recognition from the state government in 1993. This designation as the official State Outdoor Play of California formally acknowledged the play’s profound and lasting contribution to the state’s cultural heritage. It signified that the production was not just a local tradition but a representation of California’s history and artistic spirit on a statewide level.

And remarkably, in the unfolding years, a testament to the enduring power of her story and the long arc of history, the annual telling of “Ramona,” now in its one hundred and second season, would see a Native American, Duane Minard of Paiute/Yurok descent, take the directorial helm for the very first time. One hundred and two years after Helen Hunt Jackson’s passing, whose life was so profoundly dedicated to illuminating the struggles and humanity of the Native American people, the circle seems to gently close. It is as if her tireless efforts, her unwavering commitment, continue to ripple through time, finally allowing a voice from within the very communities she championed to guide the telling of their story on this very stage. It is a moment imbued with profound significance, a quiet triumph of understanding and representation. Beyond the annual outdoor production, the story of “Ramona” has also inspired numerous movie adaptations, song adaptations, and even tourist attractions, demonstrating its pervasive and enduring influence on popular culture.

Helen Hunt Jackson, a writer who understood the power of words to move hearts and change minds, faced resistance but persevered. Her legacy is not measured in victories won in her lifetime, but in the enduring power of her voice, a voice that spoke with unwavering conviction on behalf of those who were so often silenced. She reminded a nation that its pursuit of progress could not come at the expense of its humanity, a principle that lay at the very core of her devoted advocacy. And in doing so, she carved her place in the American story, a testament to the enduring power of one person’s unwavering commitment to justice.

It is a story that reminds us that even in the face of great adversity and against powerful odds, one person, with pen in hand and a heart ablaze with empathy, can indeed make a difference, a difference that can resonate across generations, even a century later

Share this Article